This summer I came across a reference in the journal Northeast Folklore to the notion that sorceresses were called fairy women in Quebec French. Unfortunately, the editor didn’t give the French word, but I assume it was la fée, like the fairy godmothers in Sleeping Beauty.

The editor seemed to be implying that the French word had lost its non-human connotations and now only signified a woman with magical powers. However, it seems likely to me that any woman with magical powers might have been called une fée regardless of whether they were a fairy or a human. In fact, the possession of magical powers seems to be the identifying factor of la fée rather than any reference to an underlying nature. This innovative meaning (la fée as a magical female) seems to point to an interesting conflation of witches and fairies in the French tradition. (The fairy godmothers of Sleeping Beauty appear to be human women in all but name, although they clearly do have magical powers. They can also be invited to human celebrations and can be young or old.)

This got me thinking also about what we mean by the word witch. Since the seventeenth century at least, we usually think of witches as humans who possess magical powers, often as a result of some satanic pact. Or we might think of them as human women who practice occult arts. But many times in the folklore, witch seems to refer to a female who acts in a very non-human and fairylike way. In the reference to the fairy in Northeast Folklore, the fairy (who the editor thought was a witch) flew through the air, accompanied by the sound of flapping wings—not very human behavior.

Although witches are often identified with human women in folklore, there seems to be a strong case for understanding some witches as magical beings rather than humans. This occurs when a story describes a witch’s magical appearance without tying her to a specific woman. On the other hand, in the case of those women who’ve become witches, have they merely earned magical powers or have they been transformed altogether, becoming something much more like a magical being? It seems to me that witch and fairy are not easily distinguishable terms.

There’s a long history in folklore, particularly Irish, of humans being identified with fairies, or perhaps being turned into them. Sometimes the spirits of dead humans who visit seers in visions or dreams are identified with fairies. There’s also the tradition of fairy changelings, which, in essence, seems to involve giving the name fairy to a human being who possesses developmental differences, giving them an uncanny air. Folklore long identified one American man (whose history I give in my forthcoming book) as a fairy, but on closer inspection of his story, one finds a rather strange-acting man with a “rolling gait” and “bowed legs” caused by Rickets disease. Folklore possibly turned the man into a fairy because his oddness suggested something other than human, causing embarrassment, perhaps, to his family. A similar process can be seen in the use of fairy as a homophobic slur, men being likened to fairies when their behavior seems unnatural or queer.

The more I read about fairies, the less I think of them as an entirely other race. The lines between us and them are so easily blurred.

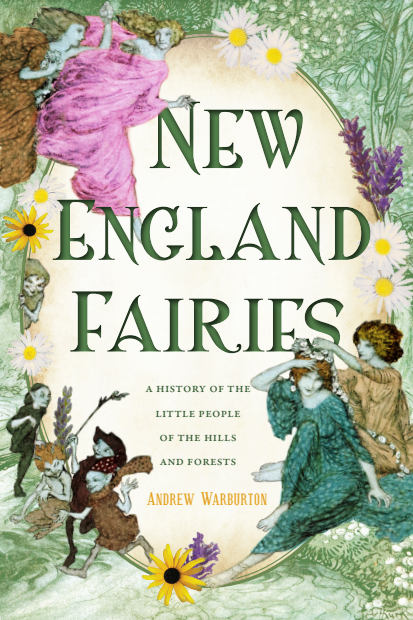

Read about New England fairies in my book New England Fairies: A History of the Little People of the Hills and Forests.

La fée from Sleeping Beauty, drawn by Henry J. Ford (1891). Public domain.

Leave a comment