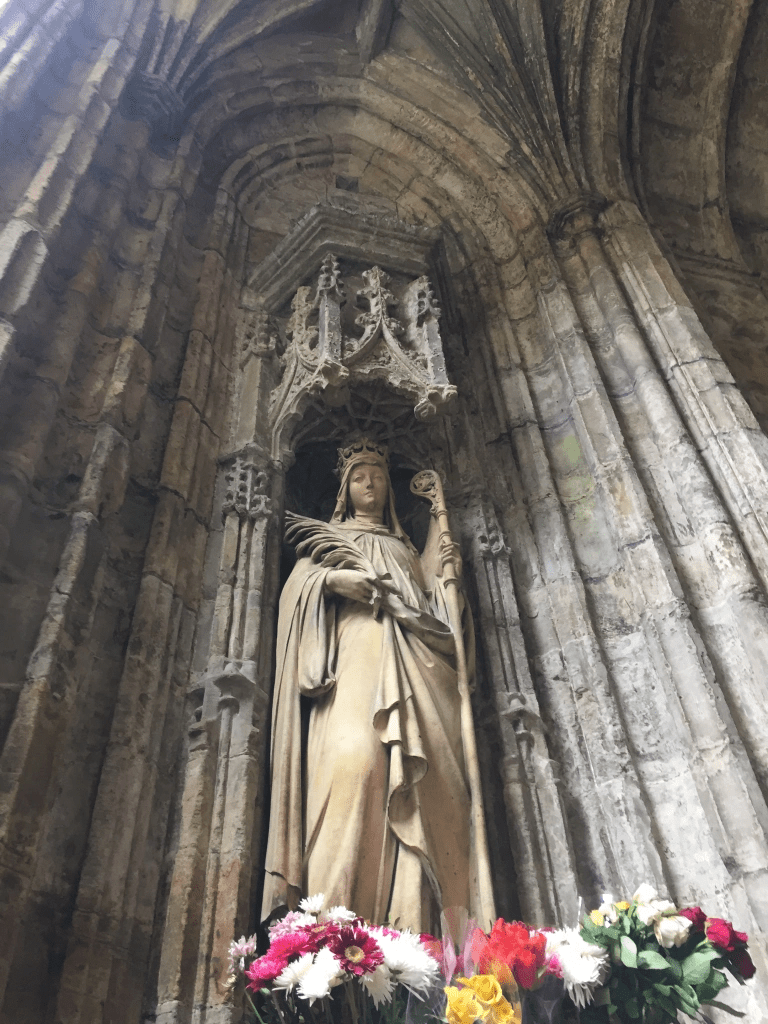

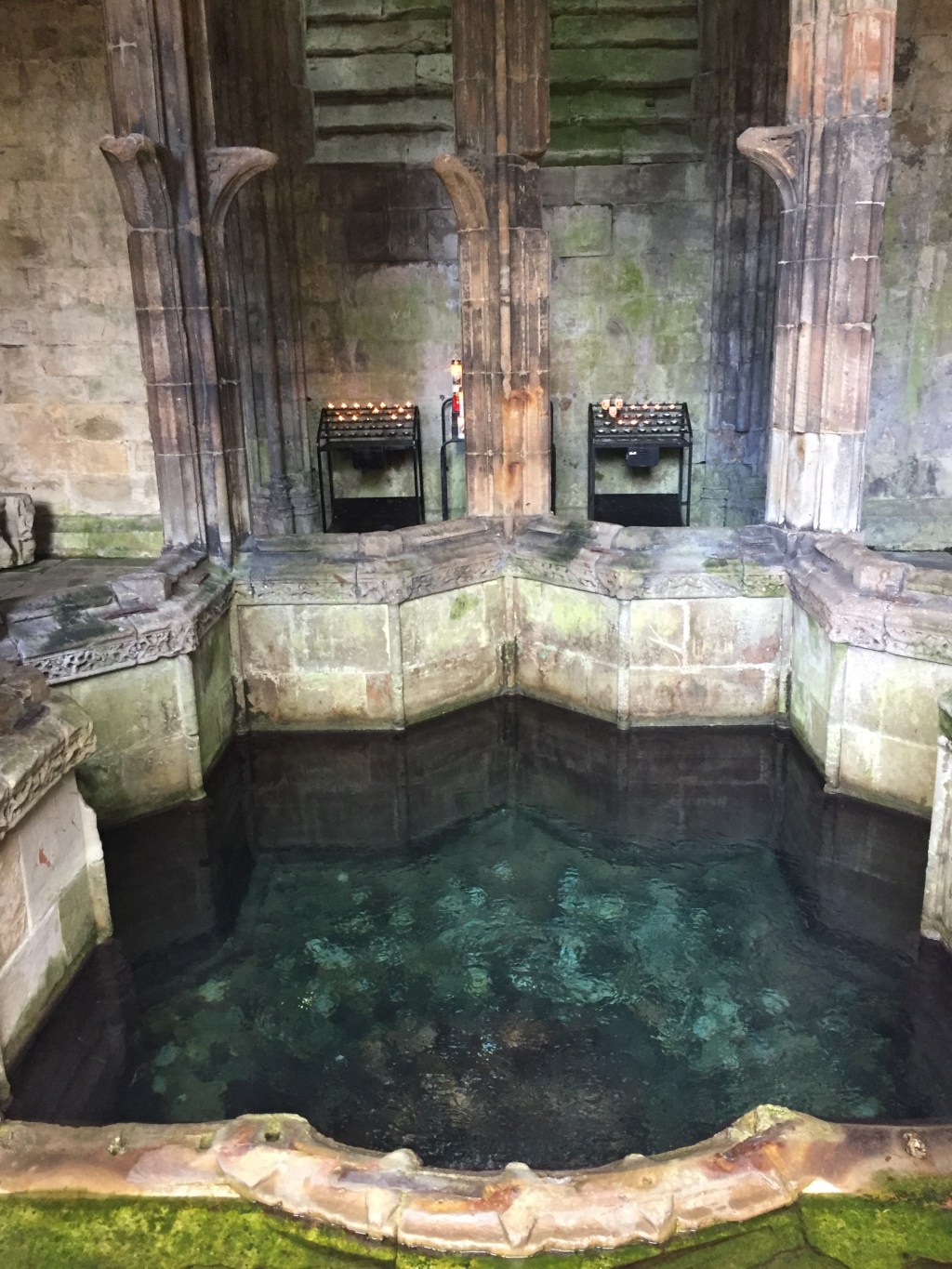

In summer 2018, I finally got to visit a location I’d wanted to see for a long time: St. Winifred’s Well in Flintshire, North Wales. The location is the site of a holy spring that attracted many pilgrims between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries. In the early-sixteenth century, a local abbot built a palatial stone structure over the spring’s source to accommodate the convalescents who came for the water’s healing properties. This structure, which still stands today, is a visible reminder of the Church’s acceptance and use of water cults, the history of which (in Great Britain) is more ancient than the Church itself.

The story of the well, if you haven’t heard it already, is that St. Winifred, a virginal seventh-century princess of North Wales, was martyred near the site. Wishing to remain a virgin, Winifred refused the advances of a local lord. He became so angry, he drew his sword and cut off her head. Where the head landed, a spring burst forth. It’s flowed there ever since.

They say that if you bathe three times in the stone pool outside the wellhead, and pray for the removal of an affliction, your prayer may be answered.

Saints and nature spirits

In his recent book Twilight of the Godlings, Francis Young draws our attention to the long history of Christian water cults in Great Britain. These cults—associated with water’s healing or sanctifying properties—can often be traced to the beginning of the Norman era and may represent the christianization of earlier water cults, British or Anglo-Saxon.

Certain questions inevitably arise: Was St. Winifred’s Well consecrated at the site of a preexisting cult, and if so, did the water’s spiritual power exist outside the authority of the Christian Church? If a prior cult did exist, and if it was associated with healing powers not conferred through an ordained priest (or the blood of a virgin martyr), the local people may have related to the spring in “pagan” ways, believing it possessed inherent spiritual powers.

Of course, there’s no archaeological evidence to suggest the spring was the site of an ancient cult, but certain facts about St. Winifred’s story are suggestive of underlying non-Christian beliefs. For example, the association between the spring and St. Winifred’s decapitated head is reminiscent of the attested pagan practice of ritually depositing representations of human heads in British rivers and springs. Furthermore, other holy wells, such as St. Anne’s in Buxton, Derbyshire (originally sacred to the goddess Arnemetia), have a clear connection to ancient cults.

If the site is the location of a former cult, one can’t help wondering what type of spiritual power the local people may have identified as belonging to the water, whether an animistic power or a divine personality.

St. Winifred at her well in Flintshire, Wales.

In his book, Francis Young offers a few examples of water-based cults from the Roman and Anglo-Saxons periods that may offer insight into the types of spiritual beings or forces possibly connected to springs such as St. Winifred’s: 1) the Roman cult of Coventina, in which votive deposits were made to a nymph or goddess associated with a healing spring in Northern England; 2) a thirteenth-century record of the archbishop of Canterbury Edmund of Abingdon, in which Edmund is described as conversing with an “angel or nymph” at a well in Oxford; and 3) a twelfth-century Norman history, in which a water spirit is described as being drawn from a well at the command of an Anglo-Saxon witch.

If a nymph did preside over the well before St. Winifred, the transition from an anthropomorphic female spirit to a saintly woman (now in heaven) may not have proved so difficult. If the transition had involved replacing a formless spirit or animistic power, on the other hand, it may have proved more difficult for ecclesiastical authorities to explain, but not impossible. The saint, through her intercessory prayer, would have become the dispenser of the spring’s spiritual power.

The Church’s relationship with water

Before we conclude that the Church’s embrace of water cults represents a “theft” of pagan practices (an argument that pagans on the Internet often seem to make about Christianity), we should examine Christian beliefs more closely. For just as water cults were an attribute of pagan religion, so water has always played a role in Christian culture.

First, baptism with water (and the analogous use of holy water in blessing) is central to Christian belief and inevitably encourages associations between water and holiness. Second, Jesus’s description of himself as a source of “living water” invites perception of water as a sign of spiritual healing. Third, Francis Young mentions the Pool of Bethesda in the Gospel of John as an example of a body of water bestowing angelic healing, thereby reinforcing the notion that a supernatural being’s power could be expressed through a source of water. Fourth, Christian theology occasionally hints at an inherent purifying attribute of water even before its consecration and use in baptism: the Englishman St. Alcuin, for instance, argued that when Adam sinned, God cursed the land but not the water, which remained in a pristine condition in anticipation of its use in baptism.1 Clearly, from a Christian perspective, water isn’t just holy as a result of its use in ritual but may also have retained a certain purity from the moment of its creation.

All these factors help explain how and why the Church was able to associate the spiritual intercession of saints with particular holy springs. Water’s role in Christian cult in Great Britain first appeared in the story of the island’s first Christian martyr, St. Alban of Verulamium, whose passion narrative (possibly recorded in the fifth century) includes an account of a miraculous spring opening at the site of his decapitation. The cult of St. Alban may have provided a blueprint for the christianization of holy wells throughout Great Britain in the medieval era.

Shrine of St. Alban, whose cult was the first to incorporate a holy spring in Britain.

Transition from spirit to saint

If St. Winifred occupies a space once filled by a nature spirit, one might well ask what the relationship between Winifred and the spirit is (or was). Some modern-day pagans might suggest they’re one and the same being—a powerful spirit known under different names and co-opted by the Church to bring non-Christian practices under ecclesiastical supervision. But even if this is the case, the process of christianization, by clothing the spirit in the likeness of St. Winifred, has radically altered people’s understanding of the supernatural being. For this reason, it doesn’t really make sense to say the two beings are the same. Nevertheless, the fact that they occupy a similar role—geographically, historically, and religiously—suggests they must share certain attributes.

Francis Young’s framework for understanding continuity between different eras may prove useful here. While the transition from a non-Christian to a Christian culture will inevitably change the nature of any supernatural being at the center of a religious cult, the context of the cult will often remain the same. In this regard, Young mentions the notion of “throwing the baby out with the bathwater.” If the “baby” in this metaphor is the supernatural being, and the “bathwater” is the historical context in which belief in that being occurs, it’s often more useful, from a historical perspective, to throw out the baby rather than the bathwater. For the bathwater is the (unchanging or slowly changing) condition in which belief in supernatural beings arises, whereas the baby (the supernatural being) is the thing that changes a lot. This is best explained through our example:

In the case of St. Winifred and any nature spirit that preceded her, the “bathwater” is the context in which both she and the spirit came to be venerated. Rather than attempting the impossible task of identifying continuity between supernatural beings of very different eras, it’s much easier and more pragmatic to identify the continuity of the context, especially when the cult’s location and the shared medium of water point to such continuity. What cultural context, then, do nature spirits and healing saints share?

The most important context appears to be a desire for healing that motivates people to seek out sources of water in both Christian and pagan cultures. The next appears to be a belief in water’s healing properties, which is common to many cultures throughout history. Finally, I’d argue that the virtues of faith, hope, and love, which Christian theology identifies as universal, are never far away when questions of religion are concerned: in this case, faith exists in the power of water to become a spiritual vessel, hope exists in the wish to be healed, and love exists in the community of bathers, pilgrims, and convalescents.

All this is to say that much continuity exists between pagan and Christian cultures. Whether you describe yourself as a Christian or a pagan, it seems to me that, throughout history, certain values and desires have bound people together at places like St. Winifred’s Well, whatever their backgrounds might be. This is because the underlying virtues we practice, and the desires we bring to a religious location, are often the same. With bigoted approaches to religion becoming increasingly popular on social media, the universality of our desires is worth remembering. Of course, some people will seek to depict this claim as weak and pluralistic, but it’s not. Being different from others needn’t prevent us from identifying the good we share with those others. When we enter the water at St. Winifred’s Well, we’re all looking for strength and regeneration.

Read about fairies in my book New England Fairies: A History of the Little People of the Hills and Forests.

- For those who like Latin, Alcuin’s words are as follows: Quare creator in Adae maledicto terrae maledixit, et non aquis? Quia de terrae fructu contra interdictum manducavit homo, non de aquis bibit, et quod praedestinavit Deus in aquis abluere peccatum, quod de fructu terrae contraxit homo. ↩︎

Leave a comment