In my book New England Fairies, I offer some French Canadian fairy stories from Aroostook County in Northern Maine. Aroostook was a destination for many French Canadian immigrants in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, so the county’s fairy lore is particularly rich. The fairy stories in the book all concern the lutin (a French Canadian elf that inhabited barns and private homes) and the feu follet (a French version of the will-‘o-the-wisp).

Here I want to offer a tale that didn’t make the book, mainly because the story’s relationship to fairy folklore is a little more complicated than other Aroostook stories. This is because the supernatural being at the heart of the tale, although called a fairy, may actually not have been a fairy at all. The editor who published the tale, as we’ll see, thought the being was, in fact, a witch.

The storyteller

The story was recounted in 1958 when twenty-four-year-old Aroostook native Ellen Pinette collected a handful of local stories involving fairies and fairylike beings and published them in the journal Northeast Folklore.

Pinette lived in the remote northern town of Eagle Lake beside the lake of the same name, so-called for its abundance of eagles. She descended from French Canadians who immigrated two hundred miles across the Canadian border to Aroostook County to practice farming in the 1880s. These French Canadian farmers brought with them many stories about fairies and other magical beings, which they passed on to Ellen when she was about fourteen years old. (One particularly memorable relative was her mother’s uncle, who lived his whole life, she said, believing in such things as fairies.)

“These stories… impressed me quite a bit and I still remember them,” she wrote in 1958. “They were told to me by my father, mother, grandparents, and neighbors, who learned them from their ancestors.”

Ellen Pinette, who recorded her community’s folklore in the 1950s.

The black fairy

The most explicitly fairy-related story Ellen shared was told to her in the late 1940s by a man of mixed French Canadian and Wabanaki ancestry who lived in the town of Plaisted, across the lake from Ellen’s home.

One year, the man said, he and his two brothers decided to make maple syrup so they could raise some money in the lead up to the Easter vacation. The brothers took their equipment to the maple groves near Eagle Lake, inserted pipes into the trees, and placed buckets beneath the pipes to receive the sap. When the buckets were full, they took them home and boiled the sap in a kettle over a big fire. So far so good.

Unfortunately, each time the brothers boiled the sap, they encountered the same problem: Just when it looked as if the liquid in the kettle would thicken, it turned back into runny sap. After this had happened a few times, one brother went into town to fetch a man who said he could help. When the man tried his hand at boiling the sap, he found the same thing happened. Eventually he gave up and went home.

One night, the youngest brother was up late boiling the sap on his own when he heard a noise outside the house like a “flapping of wings” that drew “nearer and nearer.” It scared him so much, he went to hide in bed.

The sound of flapping wings occurred every night for the next four days until the fifth night when the brothers, gathered together in the house, heard the door “bang open” and saw a “black fairy” flying in. The brothers watched the fairy fly over to the kettle and pour some kind of potion into the sap before flying away.

The brothers believed it was this potion all along that had prevented the sap from turning into syrup.

Black fairy or witch?

Ten years after hearing the story, Pinette affirmed that the brothers continued to believe that a black fairy had sabotaged their maple syrup production that year. But what exactly is a black fairy? Unfortunately, the brothers didn’t provide many details about her other than her black color, her possession of a magical potion, and the sound (flapping wings) that signaled her approach.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about the story is the fact that the editor who published it believed the fairy might not actually have been a fairy at all but was more likely to have been a witch. His reasoning for this was that the word for sorceress in Quebec French translates as “fairy woman.” (Presumably, he’s referring to the term la fée, but he doesn’t actually give the word.) Hence, the term black fairy, he thought, could have referred to an evil sorceress, otherwise known as a witch. To support this, he compared the brothers’ description of the flying fairy with European depictions of witches flying through the air.

What I find particularly interesting about all this is that it points to a certain fuzziness in folkloric depictions of witches and fairies, especially in the French tradition. I’ve explored this idea in more depth here, so if you’re interested in that topic, please check out that blog.

My biggest question about the story concerns the French term for black fairy. The men who told the tale must have been speaking in French, but Ellen recounted the story in English, substituting black fairy for the original French term. The editor implies that the original term must have been la fée noire, but I haven’t found any other instances of that term being used to refer to human sorceresses (i.e., witches). Unless there’s another term altogether in Quebec French? Please leave a comment if you have any information about this!

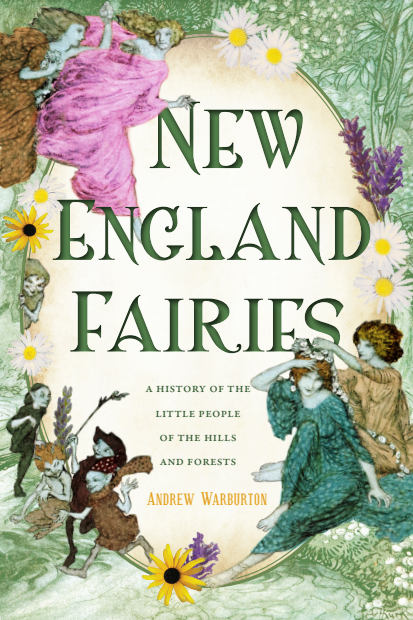

Read about more fairies in my book New England Fairies: A History of the Little People of the Hills and Forests.

Leave a comment