While researching fairy folklore outside the Northeast, I came across a rare example of an African American folktale about fairies. I’ve wondered about fairies in African American storytelling for a while, but I’ve never come across a folktale before, so it was with some pleasure and surprise that I found this one.

The story, written by children’s fiction author Virginia Hamilton, is purportedly based on “sparse evidence” of “fragmentary” fairy traditions in African American culture. That being said, Hamilton doesn’t identify her sources, so the tale may be a literary invention rather than a reflection of oral tradition. The story can be read in Hamilton’s book Her Stories: African American Folktales, Fairy Tales, and True Tales (1995). Here I’ll just share the story’s setting and its depiction of the fairies.

Hamilton grew up on a farm in Yellow Springs, Ohio, in the 1940s. It’s this rural setting that provides the backdrop for the folktales in her book. The story takes place on a Friday—a day considered unlucky (according to Hamilton) in old-time African American culture. On this day, people avoided working in the fields, instead choosing to stay home so that the day’s bad luck might be turned to “good.” The tale’s protagonist Mom Bett experiences this “good” in the form of fairies descending with the light while she sits watching the dawn from her back step:

Floating down with [the dawn] came these perfect little ones. There were glowing little girl-ones. And little boy shapes. Just the happiest, little delicate ones! They rode light streams down and sprang on the blades of grass. They lounged on the zinnias; two boy-thems lifted dewdrops and tossed them to each other. All-thems danced on the leaves. They fluttered and swayed, glowing like fireflies. Not one of them taller than two inches!

The light gathered, streamed from the blue heaven. And one perfect, floating fairy-her came down out of the tree on a light glow. She flitted before them long enough to smile at them, to swing on the cobwebs an instant. And as the sun rose, she tippy-toed up the tree from one leaf to the next, up into the heavenly light. She vanished as if she never was.

As you can see, these fairies are tiny nature spirits, smaller than the fairies of Irish or British folklore. Their association with nature can be seen in their interaction with natural objects such as dewdrops, flowers, and blades of grass, perhaps indicating the influence of Victorian (or, earlier, Shakespearean) fairies. They also appear to be crepuscular fairies, for they only appear with the first light, vanishing again with the break of day.

The fairy vision here is associated with the suspension of labor and is a gift to the tale’s protagonist, a reminder of nature’s innate beneficence. It should be noted that Hamilton writes the tale using aspects of the Gullah dialect, spoken by American descendants of enslaved people from West and Central Africa. It would be interesting to investigate whether these fairies have any precursors in Gullah folklore or in the folklore of West/Central Africa.

If anyone knows of other African American fairy stories, please leave a comment below.

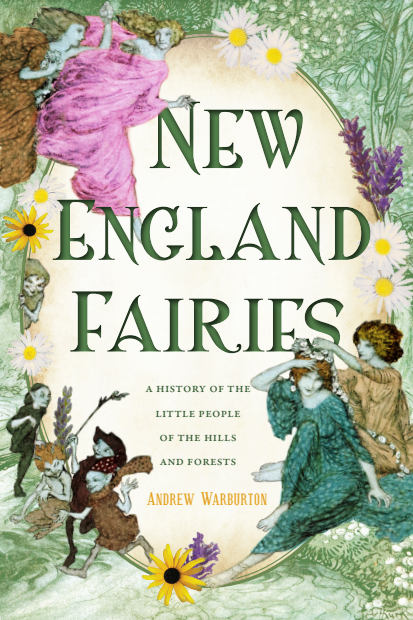

To read about more fairies, check out my book New England Fairies: A History of the Little People of the Hills and Forests.

Leave a comment