Note: Thank you to researchers Reem Kattan, Kerstie Frank, and Valmor Ildo Goulart who found sources on Dutch folklore, particularly gnome, kabouter, and goblin lore.

In 2022, when the Oxford English Dictionary chose the term goblin mode for its Word of the Year, it defined the term as referring to:

a type of behaviour which is unapologetically self-indulgent, lazy, slovenly, or greedy, typically in a way that rejects social norms or expectations.

While the notion of goblin mode was interesting at the time, it didn’t really occur to me to think more about goblins until two things came together to stir my curiosity: first, I’m researching Dutch fairy lore for a potential future project, and second, I’m attending a class on ceramics. How do these two things relate? Let me explain.

Goblins turned to stone

As part of my research on Dutch goblins, I read a legend called “Goblins Turned To Stone” in William Elliot Griffis’ Dutch Fairy Tales for Young Folks (1918) about a plague of goblins disrupting a Dutch town. Griffis apparently collected the tale during a trip to the Netherlands at the turn of the twentieth century and rewrote it for American children. In the story, goblins had been harassing the unnamed town’s residents—stealing their children, mocking them, and giving them terrible nightmares. Eventually, the townspeople went to war with the goblins: they dragged them into the sunlight so the goblins would be turned to stone. The story ends with an apparent reference to ancient dolmens (hunebedden in Dutch), reinterpreted as goblin remains:

At the first level ray (of the sun), the goblins were all turned to stone. The treeless, desolate land, which, a moment before, was full of struggling goblins and men, became as quiet as the blue sky above. Nothing but some rounded rocks or stones, in groups, marked the spot where the bloodless battle of imps and men had been fought.

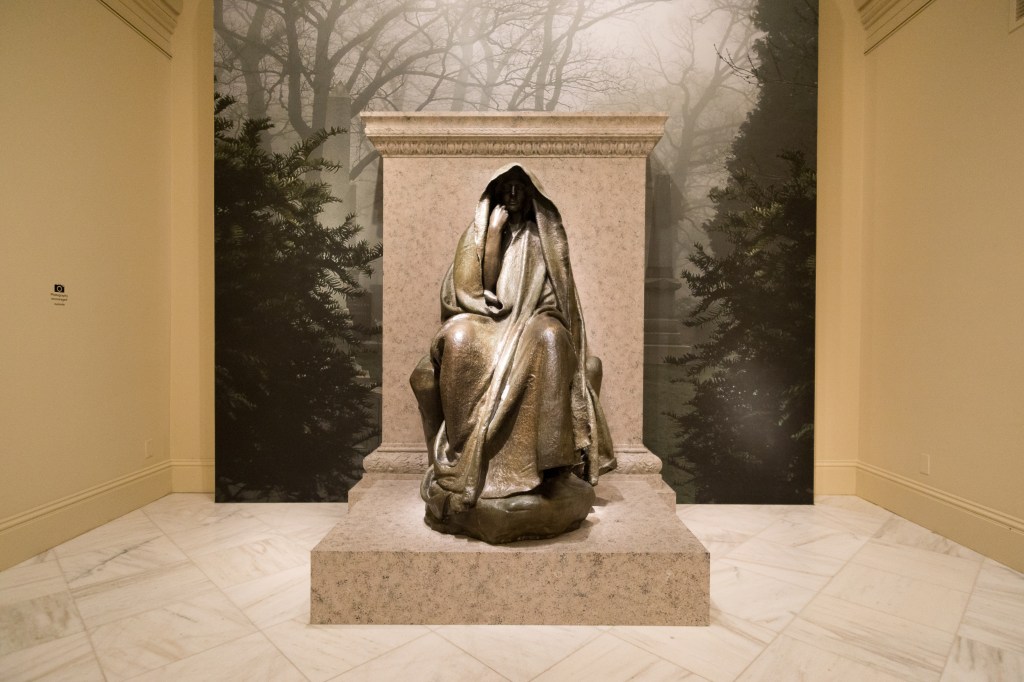

Illustration from “Dutch Fairy Tales for Young Folks” (1918). Public domain.

Because most sources about Dutch goblins are in Dutch, I had some trouble identifying the story’s goblins in terms of established folklore. Many goblin-like beings exist in the folklore of the Netherlands, including gnomes, elves (white and sooty varieties), and kabouters (gnomes who work in mines and are often friendly toward humans). To make matters worse, these beings’ traits, i.e., living underground, working in mines, and wearing red caps that make them invisible, are so similar, it’s almost impossible to distinguish between them.

In the end, with the help of writer-researcher Reem Kattan and Kerstie Frank, I figured out that the goblins in the Griffis story were probably what a Dutchwoman would call aardmannetjes, a word used to denote goblins, gnomes, or kobolds in the Netherlands. They definitely weren’t the industrious kabouters because Griffis writes about those elsewhere, although the two beings appear to be very similar (according to the story, both kabouters and aardmannetjes serve the same goblin king).

The final piece of evidence that convinced me the goblins were aardmannetjes was an 1862 source referring to the

aardmannetje, which, with the shining of the sun, turns into stone [in steen verandert] and cannot escape.

Aardmannetjes or goblins

Described as extremely ugly, with green skin, green eyes, a large head, and cloven feet, the aardmannetje seems to have existed on the mischievous end of the Dutch fairy spectrum, although some stories do depict them as human helpers. They could also travel large distances in a blink of an eye, taking the form of a flame. The word aardmannetje consists of two Dutch words—aard, meaning earth or clay, and mannetje, meaning a little male being. Living underground in darkness, the aardmannetje not only belonged to the earth but was also, by nature, cold, damp, earthy, and half-formed.

This is where my ceramics class comes in, for, based on the story of the Dutch goblins who turned to stone, we might conclude that the aardmannetje is actually a being made of clay or soil, rather like the golem of Jewish mysticism into whom the magician breathes an ensouling power. Whether this interpretation is meant literally or figuratively may not actually be that important, for the point seems to be that goblins represent a primitive, unformed, plastic state of being.

As part of the class I’m attending, I’ve had to take lumps of moist clay, form them into shapes, allow these shapes to become leather hard, and fire them in a kiln to become solid like stone. Working with the clay got me in touch with the process of forming earth into objects fit for human use. It also reminded me of the extent to which a moist, plastic medium exists beneath every hard, dry form. And I couldn’t stop thinking about goblins!

Emerging from the earth, goblins carry with them some of earth’s nature. Unlike humans of flesh and blood, goblins are—like clay—cold, damp, and hidden (this is partly because they live underground but also because they wear red caps that make them invisible). Without ever seeing the light (for they emerge only at night), they bring to light a formless life that’s otherwise impossible to see, for it remains in the darkness of the earth. For this reason, one might understand goblins as beings of arrested development, i.e., they’ve failed to rise to complete personhood. When the sun shines on them, they lose their plastic nature and turn to stone—just like clay left to dry and fired in a kiln. Despite this, their paralysis preserves an unfinished form, like clay that’s been fired too soon.

What does all this say about “goblin mode”?

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, goblin mode involves behaving in a slovenly and self-indulgent way that defies societal expectations. It asks us to turn away from society’s outward-facing expectations, which compel us to present ourselves as “finished” people, i.e., clean, well-dressed, and repressed, and instead remain faithful to the multiple ways we might exist (not just biologically or instinctively but also creatively and socially).

This doesn’t mean sinking into individualism. Goblins are not solitary beings, and to speak about a goblin mode suggests a way of being that leans toward the social even when it defies societal expectations. Otherwise, why would we need the term? For if it refers only to a private existence, i.e., one that we all experience before going out into the world, goblin mode is nothing new and has already been neutralized by social forces. To be like a goblin, on the other hand, is to remain like clay, unformed, and to insist on the plasticity of social forms, despite the solidifying pressures of society.

According to the story “Goblins Turned To Stone,” the chaotic and disruptive energies goblins represent had to be neutralized for the good of human society. This is figured by the light of day returning, freezing the goblins’ potential to take unexpected forms.

And yet despite this sad annihilation (perhaps even by and through it), the goblins remain visible to the people of the Netherlands as suggestive clumps of stone—perpetual reminders that, although “goblinhood” has been overcome, it was a living possibility and could come again:

There, these stones, big and little, lie to this day. Among the buckwheat, and the potato blossoms of the summer, under the shadows and clouds, and whispering breezes of autumn, or covered with the snows of winter, they are seen on desolate heaths. Over some of them, oak trees, centuries old, have grown. Others are near, or among, the farmers’ grain fields, or, not far from houses and barn-yards. The cows wander among them, knowing nothing of their past. And the goblins come no more.

The difference between the fired clay objects in my ceramics class and the goblins-turned-to-stone in the old Dutch legend is that, in the case of the former, the objects are oriented toward human use, whereas, in the case of the goblins’ stony remnants, no apparent use exists for the objects except to stand as reminders of a primitive, repressed plasticity.

Here we see the manifestation of a rule—that a phenomenon’s ending can give life to a ghostly continuance, especially when the ending leaves behind a memorial. Despite the goblins “coming no more,” their stones are charged with a powerful memory. The line, “And the goblins come no more,” haunts us with its suggestion that goblins came and could come again. To what extent do we, as private and social beings, allow ourselves to be haunted by the memory of goblins?

Leave a comment