I started watching Bodkin this weekend, a new Netflix show set in the fictional town of Bodkin in County Cork, Ireland.

I was fascinated to hear one of the main characters, an Irish journalist, offer the following response to two older gentlemen talking about fairies:

It’s not literal. No one actually believes there are tricksy little people around causing mischief. It’s just a way of not thinking about the things you don’t want to think about.

The character seemed to be suggesting that when something bad happens—someone dying or going missing, for instance—it’s often easier to evoke folklore (say, stories about fairies) to explain the events rather than talk about the events themselves, especially when those events are painful or inexplicable.

I’ve researched many Irish stories about fairies in the United States, most of them brought here by the huge number of Irish people who immigrated in the nineteenth century. Most of these stories concern events that the immigrants or their relatives experienced in Ireland. They often involve literal descriptions of fairies, meaning the people who told the stories really believed they’d seen or been influenced by fairies.

With other stories, it’s unclear if the storyteller was speaking literally or evoking a figurative meaning.

The problem is exacerbated if the storyteller passed away a hundred years ago or if the stories are secondhand (passed on by a relative of the original storyteller). The nature of belief is also a complicated question. People may repeat things about fairies under the influence of fairy folklore, and folklorists may interpret these statements as expressions of belief, but in reality, the words may be operating like “worn coins”—culturally conditioned statements with certain meanings attached but hardly rising to the level of belief. How many times a day do we use words we don’t literally mean, often without noticing we’re doing it?

In the case of the banshee, historian Chris Woodyard has pointed out that during the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the word banshee developed a figurative rather than a literal meaning:

The term ‘banshee’ eventually ceased to signify a warning spirit attached to a family and became a generic token of death. (“Banshees and Changelings” in the book Magical Folk.)

Woodyard’s comment offers further insight into the notion that when people talk about fairies, they may mean something else. Death is difficult to talk about. When we do talk about it, our words are often insufficient compared to the enormity of the event. Sometimes it might be easier to speak about a banshee than to speak about the reality of death.

The Bodkin character clearly took a negative view of fairy talk: she seemed to be suggesting that people ought to be talking about “reality,” not fairies. Fairy folklore, she asserts, is a way of “not thinking” about what you “don’t want to think about.” Her statement suggests fairy folklore is a form of escapism or avoidance, a weakness perhaps.

I don’t take such a negative or critical view. Perhaps people use words and ideas such as banshee because, for them, it speaks more fully to death’s reality. To talk about death using mundane words fails to grasp the reality of death, so we evoke the banshee because she knows about death, her voice is capable of speaking truthfully about it. We even call her a good woman because she mourns the deaths of our loved ones. In this sense, fairy folklore isn’t an escape from but a fuller engagement with reality.

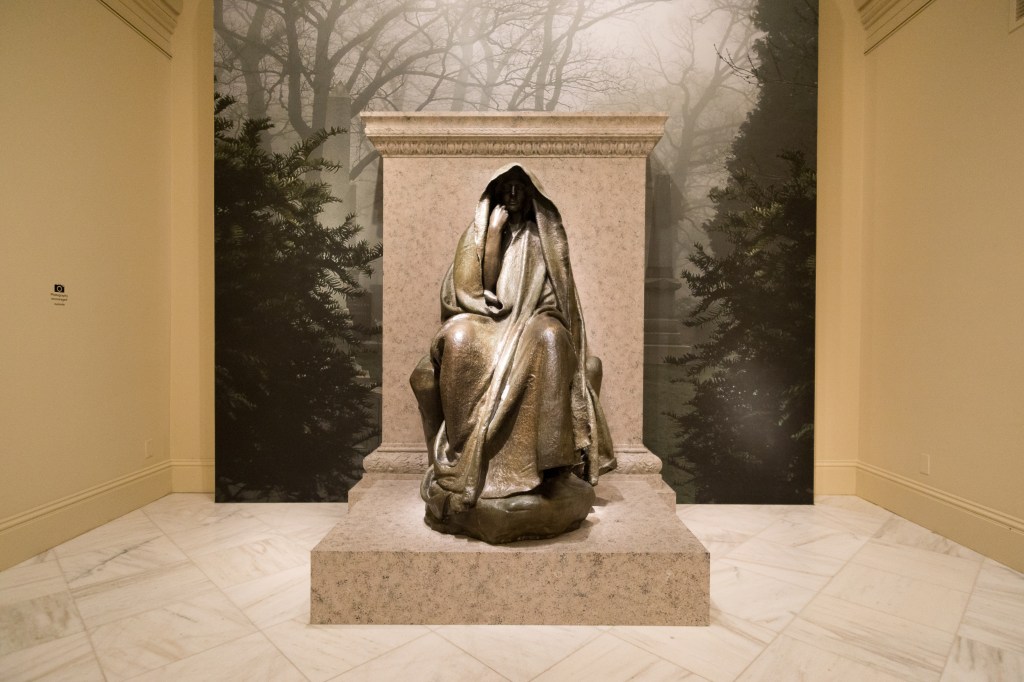

When my grandfather died many years ago, the priest at his funeral spoke the words “the peace that passes understanding,” a quote from St. Paul about the peace of God, which, according to the Christian faith, embraces our departed loved ones. When the priest said those words, I completely grasped and understood what they conveyed. They were the only words adequate to the reality of the occasion, the truest words. So it wasn’t a case of the words being an avoidance of anything; in fact, they helped me experience my grandfather’s dying more fully.

Similarly, nineteenth-century Irish immigrants in America may have invoked the word banshee to talk about the horrors of the Great Famine and the cholera epidemic affecting their communities. They did this because the banshee embodied the spiritual reality of a world steeped in death. (For the record, evidence suggests that the Irish in America did believe in banshees, and they often described her in detail, but we can never be completely sure if the words and descriptions they used had a figurative or literal thrust.)

Strictly speaking, we can no longer call such language figurative. It would be more accurate to call it higher-order language, because it describes a transcendental truth that ordinary language fails to grasp.

The Latin version of the St. Paul quote is: pax Dei, quae exuperat omnem sensum, “the peace of God which surpasses understanding.” I prefer the Latin to the English because it more readily conveys the idea that the peace of God overcomes or overwhelms all sense—not just the understanding of the mind but the receptivity of the senses and perception. Many realities exist in this life that cannot be comprehended through the use of mundane explanations or words that cleave to “fact.” Expressions and words do exist, though, that convey the incomprehensibility and transcendence of reality while also naming that reality in concrete terms: it seems to me that the banshee may have served such a purpose. To cleave to the idea of a “concrete reality” in the name of “truth” might actually be more avoidant than using expressions intended to convey spiritual realities.

Read about more fairies in my book New England Fairies: A History of the Little People of the Hills and Forests.

Image shows a replica of “The Mystery of the Hereafter and The Peace of God that Passeth Understanding” by Augustus Saint-Gaudens in the Smithsonian Museum. License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/. Photo by AgnosticPreachersKid.

Leave a reply to Andrew Warburton Cancel reply