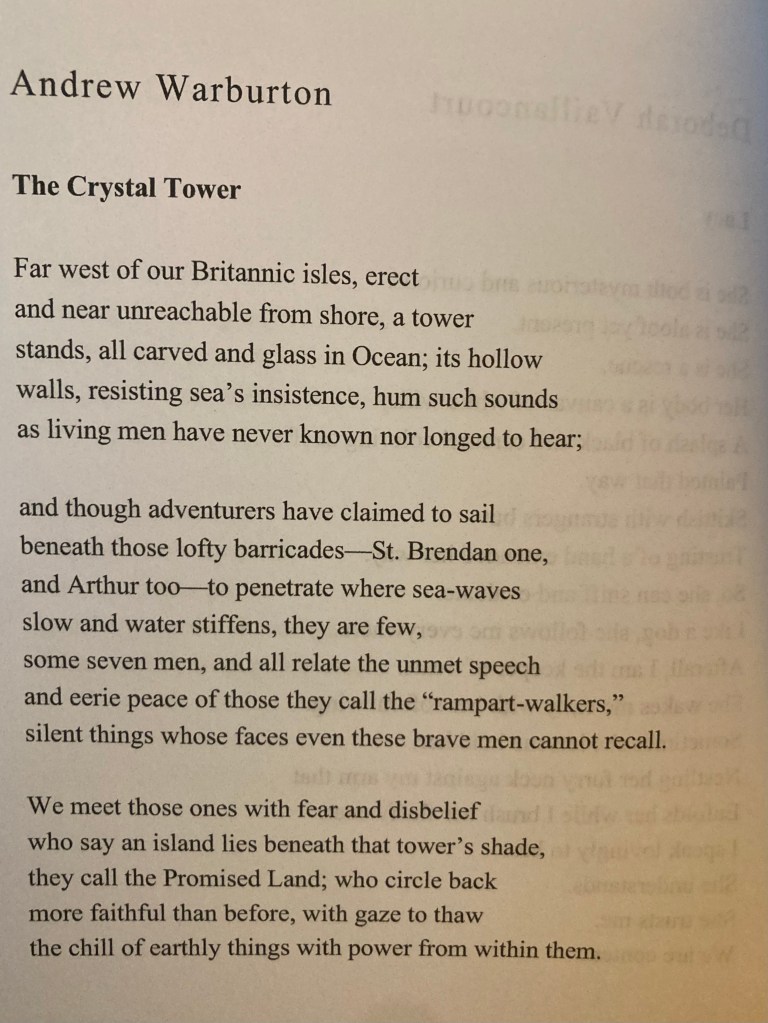

My prose poem “The Crystal Tower” recently appeared in Rhode Island Bards Poetry Anthology 2024, so I thought I’d write a short post about some of the poem’s inspirations, which had a lot to do with fairies. The poem is about human interactions with a fairy “otherworld” (the “Crystal Tower” of the poem’s title) located in the seas west of the British Isles and Ireland. Here’s the poem:

Two sources inspired my depiction of the “crystal tower” in the poem: the Welsh poem “The Spoils of Annwfn” (dated to about the year 900) and “Navigatio Sancti Brendani” (“The Voyage of St. Brendan,” possibly dated to the ninth century).

I like the texts’ descriptions of fairy citadels because they’re so otherworldly, inhuman, and inscrutable. I’m drawn to the idea that fairies might be so otherworldly that if we were to meet one or talk to one, we’d almost certainly forget what the fairy looked like or what we’d spoken about. (This type of interaction can be found in an entry in The Fairy Census where a woman describes speaking to a tall, thin fairy on top of a rock in Connecticut. When she climbs down from the rock, she can’t remember anything they spoke about).

Caer Siddi and the Crystal Column

The fairyland depicted in “The Spoils of Annwfn” is the Welsh Otherworld, called, in that language, Annwfn (literally, unworld). In particular, the poem depicts the otherworld as a fairy citadel called Caer Siddi (“castle of the fairies”) located on an island. The citadel is described as a “four-cornered castle” with “four portals,” each portal lit by a burning lamp. The citadel’s otherworldy nature is reflected in the various names given to it, including Caer Wydr (“glass castle”) and Caer Rigor (“freezing castle”). The names suggest that the citadel’s inhabitants are bereft of human warmth and softness (perhaps a reflection of the fairy nature).

The “Navigatio Sancti Brendani,” on the other hand, appears to describe the same fortress standing in the ocean, but it’s now depicted as a “four-cornered” crystal column. The two texts emerged from two very different cultures of “Celtic” Christianity, “The Spoils” from the bardic, secular tradition, the “Navigatio” from an ecclesiastical tradition. However, both seem to draw on earlier legends about a voyage to a fairy citadel. Here’s the depiction of the tower in the “Navigatio” in the original Latin and English:

Quādam vērō diē, cum celebrāssent missās, appāruit illīs columna in marī; et nōn longē ab illīs vidēbātur, sed nōn poterant ante trēs diēs appropinquāre. Cum autem appropinquāsset vir Deī, aspiciēbat summitātem illīus; tamen minimē potuit prae altitūdine illīus: namque altior erat quam āēr. Porrō cooperta fuit ex rārō conopeō: in tantum rārus erat ut nāvis posset trānsīre per forāmina illīus. Ignōrābant dē quā creātūrā factus esset cōnōpēus: habēbat colōrem argentī, sed tamen dūrior illīs vidēbātur quam marmor; columna erat dē cristāllō clārissimō.

One day when masses had been celebrated, a column appeared to them in the sea, and although it didn’t appear far away from them, they weren’t able to approach to it for three days. When the man of God [St. Brendan] approached, however, he looked at its summit, but he could hardly do this for its height, for it was higher than the air. Indeed, it was covered with a fine canopy, so fine that the ship could pass through its holes. They couldn’t understand what fabric the canopy was made from: it had the color of silver but seemed harder to them than marble; the column was of the clearest crystal.

The canopy covering the tower in the “Navigatio” is interesting because it appears to represent a veil between the ordinary world (the sea St. Brendan travels on) and the otherworld: it separates the citadel from the human world, but its fabric is so fine that the ship can pass right through it.

Another interesting aspect of the “Navigatio” is that we appear to be dealing with a Christianization of the “Celtic” otherworld, for when St. Brendan enters the “column,” he finds a chalice and patten, representing the column’s consecration to Christ, that is, his body and blood.

“The Spoils of Annwfn” also depicts the otherworld through a Christian lens, but rather than redeeming it through the presence of Eucharistic imagery, the poem demonizes it, portraying it as an icy hell. Despite this, elements of this “hell” remain ambiguously non-Christian, perhaps representing a fairyland location outside the traditional Christian cosmology. (The poet also rails against monks and their bookish knowledge, which is suggestive of the two competing traditions within “Celtic” Christianity—the bardic and the ecclesiastical).

These two traditions—the citadel as hell or the citadel as a kind of giant Eucharistic tabernacle—may represent two different ways that medieval Christian culture incorporated myths about the otherworld: The bardic tradition makes sense of the otherworld by turning it into a hell to be vanquished by a Christian hero like Arthur. The ecclesiastical tradition uses otherworld imagery as a metaphor of the paradise-to-come. Both otherworld voyages represent heroic journeys carried out by two very different figures: the saint and the king/warrior. These two figures apparently embody the two competing traditions within “Celtic” Christianity.

I’m also tempted to argue that St. Brendan’s tower of glass is the same citadel found in “The Spoils” but represents that citadel after it’s been vanquished, made holy, and emptied of its non-Christian inhabitants. The presence of the Eucharist in the fairy otherworld evidently drives out the fairies, a deed which even the Christian warrior-king cannot achieve.

The inhabitants of Annwfn

The most clearly non-Christian elements in “The Spoils of Annwfn” are its depictions of Caer Siddi’s inhabitants, which seem to draw on established bardic lore.

The first inhabitants of Annwfn mentioned in the poem (besides the human prisoner, Gwair) are the “nine virgins” who breathe upon a fire to warm the “cauldron” of Annwfn’s “king.” The identity of these virgins is enigmatic: the cauldron they guard may be one of the magical cauldrons mentioned elsewhere in medieval Welsh narratives (according to Rowan Williams). As for the virgins themselves, Thomas Green in Concepts of Arthur mentions that their number, nine, is common in “Celtic” stories and may not represent a significant element of their identity, but he does highlight their otherworldly nature: “nine women, who have their origins in Annwfyn and possess magical (fire-breathing?) abilities.” He also connects them with other groups of maidens, including the nine sisters who cared for Arthur in the otherworld and the Gallisenae, nine priestesses who lived on the Gaulish isle of Sena. Otherwise, their identity is unknown. (Fairy folklore scholar Francis Young writes about the number nine in his book Twilight of the Godlings as an amplification of the number three, the significance of which may have entered British folklore from Classical depictions of goddesses such as the Parcae and the Deae Matres).

Other inhabitants of Caer Siddi include the “six thousand men lined up on its ramparts / (Hard were the words exchanged with their watchman)” (quoted from Rowan Williams and Gwyneth Lewis’s translation). These appear to be the army of Annwfn, and the “hardness” with which Arthur’s men speak to the army’s sentinel apparently refers to the indecipherability of the sentinel’s speech rather than any aggressive exchange of words. This suggests that the inhabitants of this world and the otherworld lack a common language. (In other “Celtic” myths and stories this is clearly not the case, for there fairies often communicate with people.)

Cover image is “Kingdom of Hades,” a digital drawing by Arsen Hrebeniuk, 2022. License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/.

Read about more fairies in my book New England Fairies: A History of the Little People of the Hills and Forests.

Leave a reply to Andrew Warburton Cancel reply