I recently read Roald Dahl’s first ever children’s book The Gremlins in which he tells a story based on folklore about an imaginary being called a “gremlin,” which spread in the British Royal Air Force during World War Two. Although British pilots didn’t actually believe in these mysterious beings, they blamed them for accidents and technical problems that sometimes beset their planes, especially when no other cause could be identified. The word gremlin quickly spread throughout the Royal Air Force, wherever pilots existed in the world.

The gremlin, then, is a twentieth-century fairy that occupied a place in people’s lives a bit like the “good fairy” and the “bad fairy” sometimes blamed for fortunate and unfortunate events. This type of folklore doesn’t rise to the level of belief but gives people a way to talk about the vicissitudes of fortune, that is, everything that exists outside our control. The existence of gremlins can help us answer questions such as: Why does one car require a ton of maintenance while another car (of the same make and year) runs completely smoothly for the same length of time?

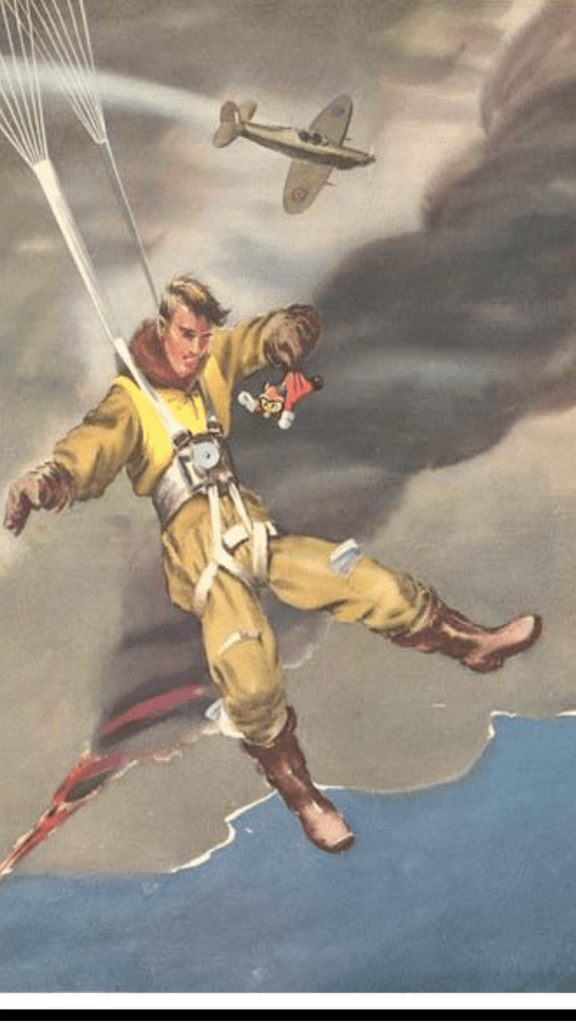

A gremlin boring holes in a plane’s wing (from The Gremlins).

Dahl’s The Gremlins is a fiction book for children but it has a lot to teach us about fairy folklore. Here are a few things the book has to say about the role of fairies in our lives (that is, if gremlins are construed as a type of fairy).

Fairies are spirits of chance and accident

The types of occurrences that the pilots in the book blame on gremlins include: holes in a plane’s wings and engine, spilled mugs of beer, pilots becoming confused so that they land outside an airfield, gas leaking from a plane, and a plane catching fire. All these events are attributed to gremlins because they defy easy explanation.

(Have you ever asked yourself why you stubbed your toe? You can come up with many explanations—i.e., “I wasn’t looking where I was going” or “I was in a rush”—but something irreducible remains, defying rationalization: After all, not everyone in a rush stubs their toe; and think about the number of times we overlook the minutiae of our movements and yet we rarely stub our toes.)

Fairies, in other words, are the inexplicable causes of chance and accident—a layer of our reality that isn’t reducible to identifiable cause and effect.

Not believing in fairies is the worst thing you can do

According to Dahl’s book, not believing in gremlins is actually the cause of much gremlin activity. At different times, a pilot in the book expresses disbelief in gremlins, causing a gremlin to prove his existence by spilling the pilot’s beer or stubbing a cigarette into the pilot’s ankle.

What does this teach us about fairy folklore?

Dahl appears to be saying the following: It’s precisely when we think we have control of fate that the fairies come back with a vengeance, upsetting our well-made plans. A system of belief that doesn’t involve a type of fairy—that is, the belief that human beings are like gods in this world—inevitably leaves itself vulnerable to upset. Far better to respect the fairies’ limits and acknowledge the domain over which they rule—namely, the mystery of our lack of control.

As Dahl states at the conclusion of the book:

He is indeed an unhappy man who goes up into the sky to fight saying, “I do not believe in gremlins.”

Perhaps it’s for this reason that I carry my lucky Cornish pixie charm to events where I have to perform. You do what you can, but let’s not pretend that everything lies in our control.

You can befriend the fairies

While the fairies may seem rather threatening because they exercise a kind of power over us, this isn’t necessarily the case. As we’ve pointed out, the fairies are at their most threatening when we disregard them. According to Dahl’s book—and wider folklore more generally—it may actually be advisable to befriend them.

Befriending the fairies has the power to transform them from wreckers of fortune into aids. This doesn’t mean, of course, that one ever has control over fairies (to think such a thing is to misunderstand their nature); one simply acknowledges their existence and acts accordingly. In Dahl’s book, the pilots feed the gremlins their favorite foods—used postage stamps—and adopt a kind of optimism that for every bad gremlin there’s a good.

At the same time, it would be an error to cleave to a philosophy in which the fairies play an exaggerated role. As personifications of chance and accident and of our inherent vulnerability in a mechanical world, the fairies are not God. They cannot bestow the most important spiritual blessings, although acknowledging them may help us develop humility and gratitude. The answer is to take them seriously without taking them seriously. A pilot would be foolish not to believe in gremlins, but he would also be foolish to believe in them too much. This is what I got from Roald Dahl’s The Gremlins.

Read about more fairies in my book New England Fairies: A History of the Little People of the Hills and Forests.

Original illustrations from The Gremlins.

Leave a reply to Andrew Warburton Cancel reply