Last week I was in Somerset, England, for my dad’s funeral. The trip evoked fond memories from the late eighties of my dad taking my brother and me to sites rich in Somerset folklore. This included Swayne’s Leap, where small stones mark the spot where highwayman Jan Swayne leapt to his freedom during the English Civil War. (The stones are spaced impossibly far apart, suggesting the leap was a superhuman feat). He also took us to the site of two ancient oak trees known locally as “Gog and Magog.” These are thought to mark the end of a two-thousand-year-old avenue of oaks leading to Glastonbury Tor. Fantastical legends suggest that St. Joseph of Arimathea walked between these trees on his way to the Tor to establish Britain’s first church. I believe my dad must have learned about these sites from Berta Lawrence’s book Somerset Legends (1973).

After the funeral, we traveled from Somerset (past Stonehenge, which is visible from the road) to West Sussex, a part of England often associated with fairies. Sussex’s South Downs (a large area of chalk hills) is said to be one of the few places in England where fairy belief survived into the late nineteenth century. My mother now lives in West Sussex, giving me the perfect opportunity to explore the region’s fairy lore.

Sussex fairies

In the folklore of nineteenth-century Sussex, the fairies are often called Pharisees. This term arose from confusion between the commonly used word fairieses and the name of the Biblical Jewish sect, the Pharisees, whom local people would have heard about in Sunday Gospel readings throughout the year. The word fairieses was unique to the Sussex dialect, for in that part of the world people tended to “reduplicate” plural words, meaning fairies became fairieses. Folklorists transcribed this word as Pharisees in the mistaken belief that the common folk had confused the two words.

Before visiting the South Downs, I’d read a story about the magical Pharisees in The Anthology of English Folk Tales (“Matthew Trigg and the Pharisees,” retold by storyteller Janet Dowling), and I’d been meaning to take a “deeper dive” into the field of Sussex fairy lore ever since. And so, with a day to spare before returning to Rhode Island, I went to the South Downs to get a taste of the area and climb Chanctonbury Hill with my mother. This particular hill looks out over Sussex, offering incredible views of the hills and plains. Climbing the steep ascent, one comes to a high ridge exposed to chill winds, with scatterings of gentle, cud-chewing sheep. It was good to be in the English countryside again.

I chose this particular location because the hill is crowned by the atmospheric Chanctonbury Ring, a circular earthwork surrounded by trees. In Ireland, hillforts like Chanctonbury are called fairy forts, and in England, too, they’re sometimes associated with fairy activity. The earthwork was built as a hillfort during the Iron Age and was in use as such until about the fourth century B.C. Some five hundred years later, the local Romano-British people (probably the Regni tribe) built two temples at the site. It’s not known what deities were worshipped in the temples, but based on the Ring’s altitude, whatever cult existed was probably celestial in nature rather than chthonic (that is, of the underworld).

The Ring’s ancient history wasn’t what drew me to the site. I was interested in the Ring because it’s been associated with fairies and other folkloric beings since at least the nineteenth century. In 1878, folklorist Charlotte Latham published the following tale of a farmer’s interaction with the fairies in a village below Chanctonbury. I share it here in full:

A farmer at Washington, who had been often surprised, on going into his barn early in the morning, to see large heaps of corn that had been threshed during the night, determined at last to sit up, and discover, if possible, who the kind friends were who worked so hard and well for him whilst he was taking his rest. So creeping to the barn-door, and looking through a chink in it, he was astonished at seeing two little fairies working away with their fairy flails, and only stopping for an instant, now and then, to say to each other, “See how I sweat! See how I sweat!” . . . The farmer in his delight forgetting that fairies are offended if a mortal speaks to them, cried out, with a loud laugh, “Well done, my little men” and instantly (the story says) the little men uttered a wild cry and disappeared, and never more were know to resume their work in that barn.

Fairies have been spotted in other locations near Chanctonbury as well, including the six-mile-distant Harrow Hill (said to be the fairies’ last home in England) and two more hillforts (Cissbury Ring and Tarberry Hill) where the fairies were thought to dance on Midsummer’s Eve.

Chanctonbury Ring is sometimes included in lists of locations where the fairies are known to dance, but the earliest collections of folklore don’t actually mention this. Instead, we find variations of a legend about the Devil. This legend states that if one circles the ring three times (sometimes it’s seven or nine), the Devil will emerge from the Ring and offer the walker a bowl of porridge or soup. Based on the testimony of one of my mother’s friends, who visited the Ring as a girl guide many years ago, this legend remains alive among locals today.

Other stories associated with the Ring include people seeing UFO-type lights, encountering ghosts, and hearing unearthly screams.

Chanctonbury Ring atop Chanctonbury Hill

Chanctonbury’s fairy muse

Later references to Chanctonbury Ring in the realm of literature point to an interesting development of Sussex fairy lore. Within a few decades of Charlotte Latham publishing the fairy stories of Sussex folk in her book West Sussex Superstitions, Sussex poet Charles Dalmon wrote “The Sussex Muse” (1895), in which he drew on the South Downs’ reputation for fairy hauntings, producing something related but quite different. For an understanding of Dalmon’s work, I’m indebted to Peter Brandon’s book Sussex Writers in Their Landscape (2024).

Dalmon’s “The Sussex Muse” is clearly in conversation with the fairy stories of Sussex folk (the “villagers,” “farmer,” and “shepherd” he mentions in the poem), but he transforms the Sussex “fairy” into an elevated spiritual force—the “Muse” of the poem’s title. For Dalmon, the simple folk who “practise chimes” in the local church, who sharpen their “sheers” at the “grindstone” and perambulate their “orchards,” appear to live in harmony with a fairy Muse whose power suffuses the natural world. They do not question the existence of fairyland or the nearness of the Muse because they’ve never actually been separated from her, their rural society existing in union with nature. The educated poet, on the other hand—alienated by his intellect, his time in urban landscapes, and his proficiency with language—no longer abides in harmony with the Muse or nature and experiences an anxiety that he might lose her at any moment. As a result, he’s forced to ramble in the hills, “call out” to the Muse for inspiration, and even “earn” her love. The Muse whispers back:

“You who have stood on Chanctonbury Ring

So many times at sunrise, calling me

Out from the northern pastures of the Weald,

Or southward from the slopes toward the sea,

Not vainly unto me have you appealed,

But I would have you sing,

Before I love you, something soft and clear

And full of countryside simplicity. . .”

For a poet like Dalmon, belief in the Sussex fairieses (the “merry elves” that make “the meadows ring with their delight”) represents a poetic vision of the world that’s “soft and clear” and full of “simplicity.” However, in filtering this vision through his romantic (and ultimately Classical) ideas about the Muse, as well as his own alienation, he transforms Sussex fairy lore, portraying it not as it was but as he wishes it to be: an antidote to modernity.

The difference between the beliefs of the common folk and Dalmon’s abstract “Muse” opens up the question: to what extent does the nature of fairy belief change when it’s invoked as an antidote to modernity, whether the loss of an agricultural mode of life or separation from nature? Arguably, if belief in fairies becomes an “antidote” to modernity and a way to access spiritual power (Dalmon’s “Muse”), it ceases to be what it was, for it will always bear a trace (even a negative trace) of modernity within it. This question is particularly relevant in an age when fairy belief appears to have developed novel spiritual dimensions while representing itself as “in continuance” with the past.

The Muse’s request of the poet is paradoxical, for she specifically chooses a man she’s long since abandoned to the influence of modernity, asking him to sing a song of “simplicity.” According to the logic of this poetic inspiration, the simple folk who hear the “merry elves” in the “meadows” are unable to sing a satisfactory song despite existing in union with the Muse. Instead, the Muse requires the educated man to learn her “song” and win her “love,” having separated herself from him in the first place. In this, we see an interesting dynamic of poverty and fullness playing out: whereas the country folk are rich in their union with nature, the poet experiences the poverty of the Muse’s absence despite being rich in learning. In this, he differs from the magician whom I wrote about here, for whereas the magician’s education in the occult arts gave him power over the realm of fatality, the poet’s learning leaves him powerless. He must strip himself of this learning to earn the Muse’s love, but it’s precisely this humbling that makes him worthy of that love. Instead of exerting power like the magician, the poet empties himself, calling out to the Muse in his poverty.

Nevertheless, there appears to be something false about this depiction of the poet, for if the Muse’s “song of simplicity” were really that “simple,” why wouldn’t the Sussex country folk sing it better than the poet? In fact, in one sense, they do, for the country folk sing this song through the lives they live: their whole way of life is a song dedicated to the Muse. As for the poet’s song, the fact that the common folk cannot sing it (that is, they cannot write his poetry) suggests that the song may represent an ersatz simplicity: is it the product of the poet’s self-deception, in which he consoles himself while experiencing alienation from the fairy Muse and his fellow men and women? This would mean that the poet’s pretensions are illusions.

Or can the poet’s song be a higher level song, incorporating the lessons of separation while returning successfully to nature and the Muse? If the poet’s song is to become more than self-deception, it must find its place among the common folk, reflecting the song of their lives through the higher-order language of poetry. If the poet is able to produce such a song, he will successfully have reconciled the difference between himself (as an educated poet) and the rural laborers he loves, for he and they will be held together in the Muse’s embrace. This appears to be the motivating desire of Dalmon’s poetic inspiration.

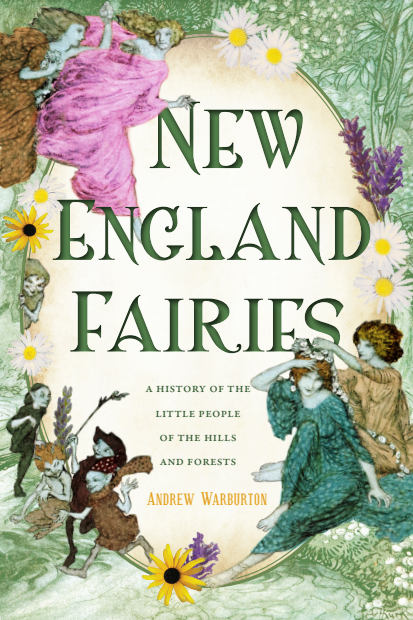

Read about more fairies in my book New England Fairies: A History of the Little People of the Hills and Forests.

On Chanctonbury Hill

Leave a reply to lisemayne Cancel reply